Week 9: Research Bias and Work Incentives

During my undergraduate studies, I was frustrated by how much my economics classes focused on wealth. The success of an intervention would be measured by how it impacted someone’s wealth. While increasing someone’s wealth can have positive impacts, I felt like only looking at that metric misses a lot. There are many ways someone’s life might be improved that are not related to their monetary wealth. The argument for using wealth was that it is easier to measure. It is harder to reliably measure mental health or happiness.

My interest in pushing for other metrics besides wealth, comes from my specific experience in the world. In my life, if you only look at wealth, there is a lot of richness that is missed. Changes in my income have had a smaller impact on my well being when compared to other changes. My experience is not shared by everyone though. I grew up in a family that never struggled to provide for me. When I receive marginally more money, it does not make much of a difference. For others, an increase in wealth can have a much larger impact than it does for me.

What I find to be meaningful research is impacted by my own experiences. Using other metrics besides wealth is probably still an important thing to push for. But due to my own experience with wealth, I am probably over indexing on my own experiences when thinking about research directions.

Since my personal wealth is much higher than what I actually need, I donate around 10% of my income to charity. One charity that I have been particularly impressed with is GiveDirectly. They have a clear and important mission, cash transfers to people in need, and do an impressive job of measuring the impact of their programs.

Recently, a friend told me about a study from the Happier Lives Institute which found that another charity, Stronger Minds is 12X more effective that GiveDirectly. Strong Minds provides group therapy to women in Africa who might be struggling with depression. I was really excited about these findings. These findings lined up with some of my pre-existing believes. They show that by focusing on mental health there is a way to improve people’s lives dramatically. After a quick glance, I added Stronger Minds as one of the charities I donate to.

As a few weeks went by the nagging suspicion kept popping up that it is hard to believe that group therapy is 12X more effective than cash transfers. The findings were aligned with my existing biases so it was easy for me to just accept them. But 12X is such a huge difference. And 12X more cost effect at what? I decided to look deeper into the research.

Reading HLI’s work in more detail made me reflect on how much my existing world view can impact my understanding of new evidence. After doing the reading, I do not have confidence that we can currently compare the impact of cash transfers with psychotherapy. It actually feels a little irresponsible to say Stronger Minds, is 12x times more cost effective than GiveDirectly. Since, the majority of people who interact with HLI will not dive deeper than that broad takeaway, I am disappointed in HLI. That result is on HLI’s front page, which implies they would only make such a statement if they are quite confident it is accurate.

I spent a few hours across a couple of days reading HLI’s findings (summary, cash transfers, psychotherapy) to understand more about their approach. To evaluate the interventions they used two measures, Subjective Well Being (SWB) and Affective Mental Health (mHA). SWB involves directly asking individuals about their well being. MHa is based on asking questions related to common mental health disorders such as depression. For both interventions they do a meta-analysis by combining results from many different papers. Their outcome of interest is standard deviations of improvement as a result from group psychotherapy or a cash transfer.

As I first started reading HLI’s work it made more sense how they could find such a large effect. Psychotherapy being 12x more cost effective can be broken up into two components. HLI estimates group therapy is 3x more beneficial than cash transfers while being 4x less costly. While a $1000 transfer will cost more than $1000 dollars (~$1200), delivering group therapy costs only about $300 per person. The finding of 12x cost effective feels more plausible knowing that a large portion of it is due to therapy being cheaper than monetary transfers.

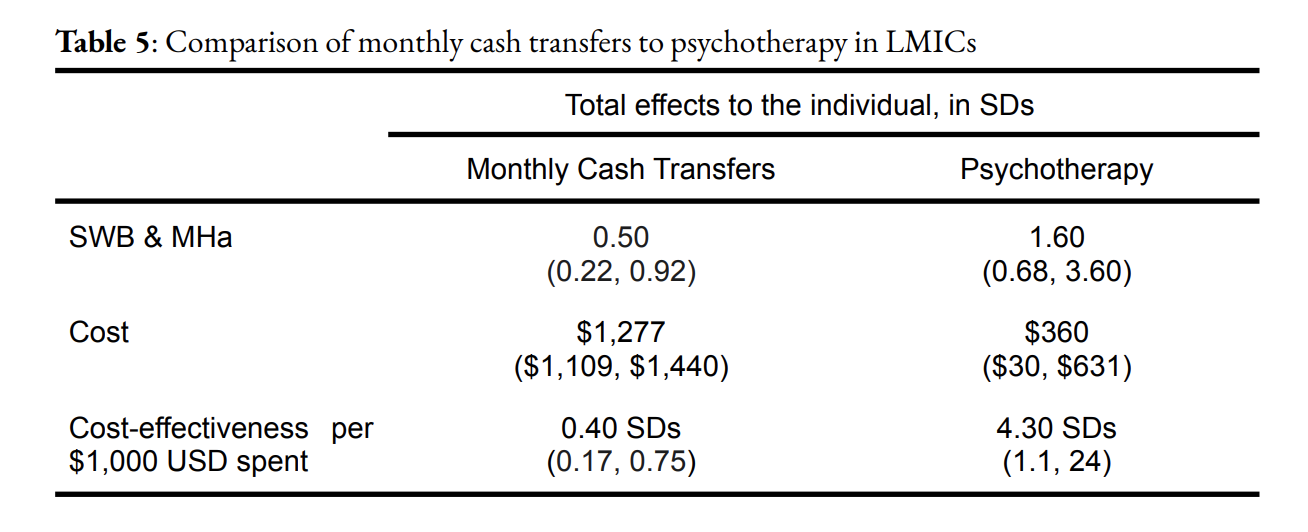

Looking deeper at HLI’s estimates though is where my confidence in their findings began to fall apart. As I mentioned, to estimate cost effectiveness they estimate both the benefit and the cost. Their key estimates can be seen in the table below. The confidence intervals on these estimates are quite large, especially the psychotherapy ones! The authors actually state that their estimate for how much more cost effective psychotherapy is could be anywhere from 4x to 27x. That is a really huge range! There is more variation in their estimate of the benefits so thats where I focused my energy next.

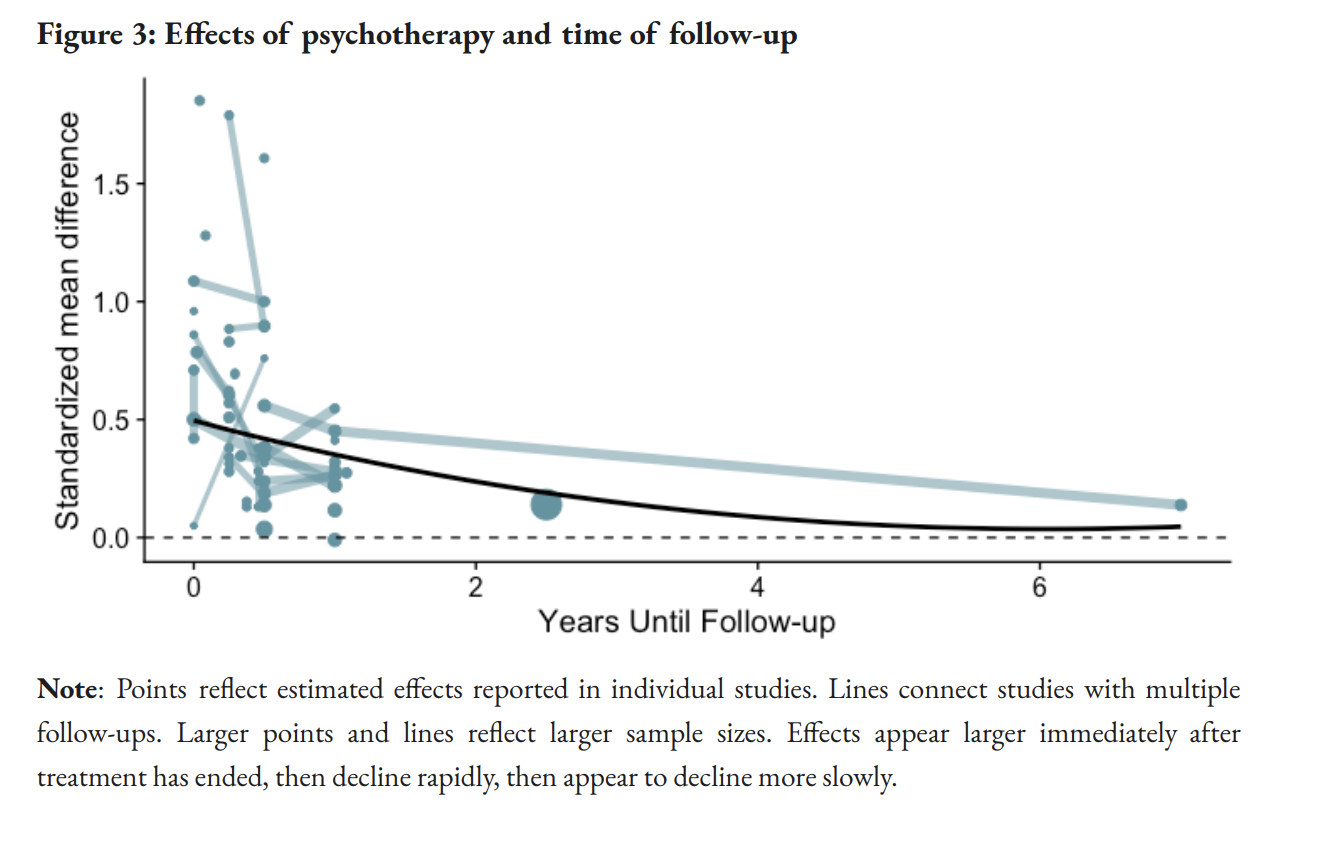

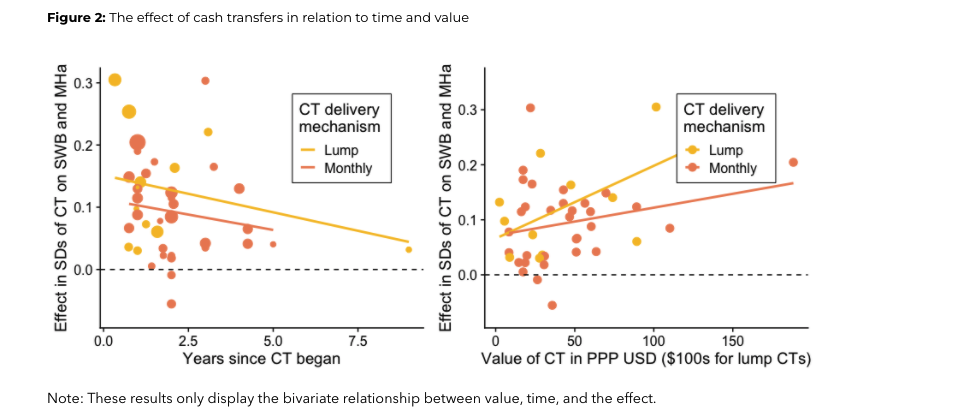

The amount of variation in the measured benefit of these interventions makes me believe that HLI’s confidence intervals might be too small. To estimate the impact of both interventions HLI runs some simple linear regressions. For psychotherapy they regress benefit on years since intervention with an intercept term. For cash transfers they regress benefit on amount of money and years since receiving the transfer. The graphs for both of these regressions can be seen below:

Looking at both of these graphs, it immediately jumps out how noisy they are. Across all of the different studies, there is so much variation in how much benefit participants get. The other thing that jumps out is how little data there is further in time from the intervention. There are a lot of data points for both interventions in years 1 and 2. As more years pass though, there are almost no data points. Since there is so much noise in the early years and only a few points further out, our regression estimates will be largely driven by those points that are further out. If those points were removed, the results would be quite different. This means the generic confidence intervals that come from a simple linear regression will be incorrect since those points are having such an outsized impact.

It is easy to justify not removing these outliers because they make the regression result line up with our basic intuition. It makes sense that both interventions should have less of an impact the further away we are from the intervention. It also seems logical that a larger cash transfer should have a larger impact. For both regressions, if we removed the outliers the results of the regression would be less intuitive. For cash transfers, if we remove those couple of studies there would be no relationship between time since intervention or amount of money and benefit. In the psychotherapy papers the authors even acknowledge how sensitive their estimate is to these outliers

Are our estimates sensitive to outliers? Baranov et al., (2020) has an unusually long follow-up. If we exclude it from our analysis the estimated total effect is reduced by around half.

After looking at the graphs above, my confidence in the results of the papers completely disappeared. The findings are built upon both of these regressions. If the results from these regressions are changed, then the whole paper is quite different. Using the graphs, it feels really difficult to compare these two interventions with a lot of confidence. Seeing all that variation makes me think we need to understand some of the factors causing those differences before we can feel confident estimating the impact of the intervention broadly.

Besides not having faith in the key regressions, there are a couple of other things that made me question my believe in the research.

The studies that the authors use are from many different countries, looking at many different different populations. The same intervention will have a very different impact depending on which population it is targeting. Psychotherapy will be more effective for some than others. Similarly, $1000 dollars will have a different impact depending on the person. It is not clear to me that these two interventions were being applied to the same population or how the findings from the paper would apply to other populations.

While I was doing more reading I realized that when HLI states the 12x more cost effective number, it is not directly stated what the charity is more cost effective at. Their statement implies that StrongerMinds is a 12x better charity than GiveDirectly, but that depends a lot on what the goal of the charity is. StrongerMinds is directly focused on improving mental health through psychotherapy. While cash transfers can improve mental health their are many other positive impacts they could also have.

In a lot of ways it feels like the research was set up to find that group psychotherapy is more cost effective than cash transfers. The outcome of interest is the one that psychotherapy is directly targeting. StrongerMinds probably applies their intervention to populations where they think it will have the largest impact. Since GiveDirectly measures their success differently they are probably not targeting their interventions to have a large impact on mental health.

While I really appreciate HLI’s approach of measuring an interventions success using a mental health measure, I feel uncomfortable with the general statement they made comparing the cost effectiveness of the two interventions. To confidently make a general statement about cost effectiveness, it feels important to look at a few different outcomes of interest. There might be other outcomes we care about such as physical health, children’s health or education levels that are moved differently by the two interventions.

After doing the further reading, I am convinced that both Stronger Minds and Give Directly are effective charities and I will continue to donate to both of them. The two charities have slightly different problems they are approaching with different techniques. I think there is some weak evidence that Stronger Minds might be more cost effective if our main goal is treating depression. There are lots of open questions though, about how effective both charities are and why there is so much variation in their effectiveness.

Just as my own biases led me to immediately believe HLI’s findings, when doing any type of work we are susceptible to our biases. Our biases make it more likely we do work that is misguided or not completely accurate. To wrap up this piece, I am going to examine how some biases might led to faulty work. I also believe that some of the structures around academic research magnify these biases making it more likely that incorrect findings are shared. Taken together, we actually should expect that a non trivial amount of academic research will be incorrect or misleading.

When sharing work, there is always the difficulty of making it understandable to an external audience. A researcher will always be the person closest to their work. To share that work with others it is necessary to summarize by focusing attention. There will generally be an incentive to communicate findings strongly and over confidently. As we saw with HLI their headline communication of 12x more cost effective does not feel representative of all the details and nuances of the work. Looking at the the details, the actual story is one of variance and uncertainty. This incentive to over communicate results is both internal and external. Internally, We want our work to be meaningful and to have an impact. Work that does not have a finding feels less important. Externally, others often have an influence on what we are working on. If a certain direction is not showing promise, then resources might be allocated away from it towards something else.

This pressure to sum up findings in one digestible and meaningful takeaway, might be one reason that significance testing is such a popular paradigm. Significance testing provides a singular value that determines whether or not we have made a finding. Significance tests are known to be quite arbitrary. Through changing our specification or cutting the data in selective ways it is possible to find a significant result. Significance values also give a false sense of precision in results. Results are often reported to two decimals when our actually precision is much less than that. When looking at HLI’s results, using significance testing implies there is a really meaningful result. But when I looked at the core graphs, the actually story of variation and uncertainty became clear. The use of statistical significance to summarize research results feels more harmful than the benefit it gives of easier communication.

These biases / pressures are not unique to academic research, they are present in all work, but academic research has some structures which I believe magnify these biases. The success of a researcher is measured by their ability to publish in selective venues. The final product of research is considered the publication of the paper. Any work that does not contribute to the publication of a paper is not considered valuable. This further incentives researcher’s to make sure they have made meaningful findings. Furthermore, after the paper is published the work is considered complete. There is not as much incentive to solidify the work or build upon it. Occasionally replications of work are done, but these are not considered to be that valuable of work.

The decentralized nature of academic research and its reliance on peer review means that work is not as thoroughly scrutinized as it could be. The main way researchers get feedback on their work is through peer review when they are submitting their work. Researchers actually have some incentive to keep their work secretive so that another researcher does not publish something similar before them. This means by the time they are getting feedback, their work is near completion. Only getting feedback once it is nearly finished limits the types of feedback that can be given. Furthermore, since peer reviewers make the publication decision, the paper is structured to convince them of the merit of the work rather than about getting good feedback.

Even with these structures, I believe that a lot of really good and meaningful work is done through academic research. There are opportunities for improvement though that could mitigate some of the impacts that biases have on results.

For myself, recognizing how much my biases and incentives impact me has been really important in improving the quality of my work. There are a couple of lessons I have learned which I trying to bring with me in the work that I do

- With every piece of work, I am going to be biased to find a certain result. It is important I recognize which result I find desirable and challenge myself if I end up finding that result.

- I use graphs as much as possible and try to look at the same result in a few different ways or with a few different methods. For me to feel quite confident in a result I want it to show up in many different places and also for it be quite large.

- In my communication, I try to accurately convey how confident I feel about something.

- The best thing I can do to overcome my biases is to put my work in front of others and get their views. Others will have different biases then me and generally they do not have an incentive to have a finding. Their name is not attached to the work. I try to do this early and often and do it with many different people.

- Work is never actually complete. It should be followed up on and used. It must be continued to be built upon and constantly reevaluated. It is a recurring cycle.